Ten weeks, seven insights: Interns share takeaways from a summer with CHCI

Four University of Pennsylvania graduate students recently completed 10 weeks of immersive learning and participation in health care improvement projects through an internship at the Center for Health Care Innovation (CHCI). Cathy Zhao and Cameron Leung, who are in the Integrated Product Design master’s degree program, and Aaron Wang and Nathan Orwig, medical students at the Perelman School of Medicine, spent the summer putting CHCI’s methodologies into practice and lending their skill sets to projects centered on home health services, clinician experience, records collection, neurology patient telemedicine screening, and more.

As the program wrapped up in August, the interns reflected on their experiences in the health care innovation space. A handful of their learnings are summarized here.

Innovation and uncertainty go hand in hand

“One lesson I had was ‘lean into the mess,’” Zhao said. Projects can feel daunting at first, she said, describing how she and a CHCI colleague had spent hours making sense of information they had uncovered and getting ideas down on a whiteboard. Despite the discomfort, she said, “It pushed me to lean into the divergence.”

Wang agreed. “A takeaway that I’d like to bring with me throughout my career is that it’s okay to be uncomfortable with uncertainty,” he said. “On a lot of these projects, there was too much information to process. Sometimes, it’s best to take things one step at a time and move forward even if you don’t know all the answers to all the questions.”

Constraints are your friend

One strategy that Zhao found helpful for managing messiness was applying constraints. In designing tests for a clinician experience project, for example, she learned she could prioritize goals and set limits: Version one of a pilot might aim to fulfill a set of core requirements, whereas later pilots could incorporate additional considerations – and desired but non-essential objectives might not be part of pilots at all.

Test fast, learn fast

Along the same lines, the interns learned firsthand the value of prototyping and rapid validation. Tasked with developing a screening tool for telehealth services, they built a patient questionnaire. But when they tested it out, some answers surprised them.

“That was a really informative process,” said Wang. “No matter how much we prepared or thought about what questions we wanted to ask, once we actually engaged with patients, we learned a lot and were able to make more purposeful and meaningful edits to the survey.” Thanks to those findings, the interns were able to optimize their form to collect crucial information more effectively.

Iteration creates creativity

Orwig, who supplied a trio of projects with computer science expertise, found himself connecting with the concept of creativity – which looms large in the innovation space yet often feels elusive, especially with analytical tasks.

“In computer programming, I use iteration all the time,” he explained. “I create programs that can do better and take in more data; I can add more; I can cut things out. The model is becoming better at creating connections between things. And that iteration, it’s a key form of causing creativity.”

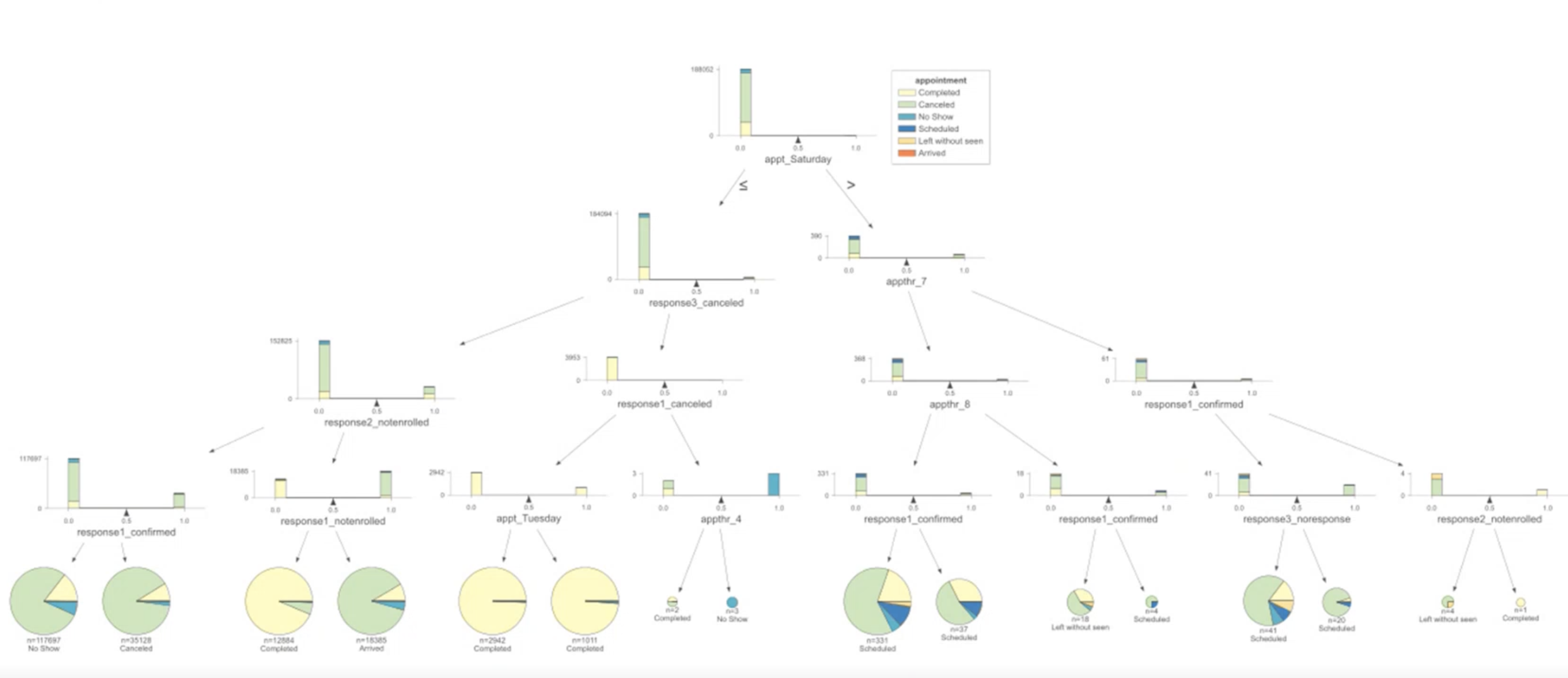

Iterating and applying his creativity, Orwig developed a model to predict patient responses to questions about opioid usage, which could assist in scaling opioid-related interventions. He also analyzed data around missed appointments and created a predictive model that could be leveraged for investigating and preventing no-shows.

Communicate in ways that work for your audience

Among Leung’s tasks was conducting a photoshoot for Check-EN, a program for patients on enteral nutrition, to create image-rich guides illustrating the equipment the patients need and the steps they should follow. Contributing to the guide showed him the importance of visualization, he said.

For the Cavalry home services project, Leung learned and practiced other communication skills: He interviewed patients, worked on a slide presentation and brochure, and distilled information into a one-page summary for doctors and leadership. The need for brevity was striking for him and emphasized a perspective he thought was worth keeping in mind for future design and engineering projects.

Electronic does not equal efficient

While reviewing the literature on records collection, Wang learned that, counter to what one might assume, electronic health record tools such as structured data entry do not always enhance information collection. “If you don’t develop your SmartForm in a smart way ¬– with user workflows and desired outcomes in mind – and you don’t engage the people who are actually using the form, it might actually take more time than using free text,” he explained. Likewise, electronic consent can require more steps and time than a printed form handed out at the clinic. In light of those findings, Wang lauded the records collection team for “doing a great job engaging their stakeholders and implementing tools in the right ways to actually improve workflows.”

Don’t overlook the human element

Leung and Zhao had the opportunity to observe the CHCI “Blue Coats,” who are working to enhance clinician experience and have cultivated relationships with the emergency department staff they have sought to help. Both took note of how the Blue Coats made people feel heard and appreciated. “Being in the environment with them really brought home the value of that project for me. I could see the impact,” Leung said.

Additionally, this and other projects Leung worked on “put into perspective how hard health care can be for clinicians,” he said. “Often, you only see the patient side.” It was a reminder to him that in engineering and design, there are always humans involved whose needs matter but tend to be overlooked.